The access to, use of, and quality of health care can vary based on socioeconomic status, which can be measured by income, education, and/or occupation.1,2 Socioeconomic factors can be associated with various health outcomes, one of them being surgical site infection (SSI) which affects up to 5% of surgical procedures nationwide.3 However, the association between this status and the presence of SSI is still being studied.4 The studies below illuminate socioeconomic status and healthcare interactions based on a few selected social factors.

1. SSI Rates after Colectomy and Abdominal Hysterectomy for Specific Genders and Races4:

A cross-sectional study took place at general acute care hospitals across the U.S. analyzing 149,741 adult patients undergoing colectomies or abdominal hysterectomies. Of the 90,210 patients undergoing colectomies, the mean age was 63.4 years consisting of 54% females.

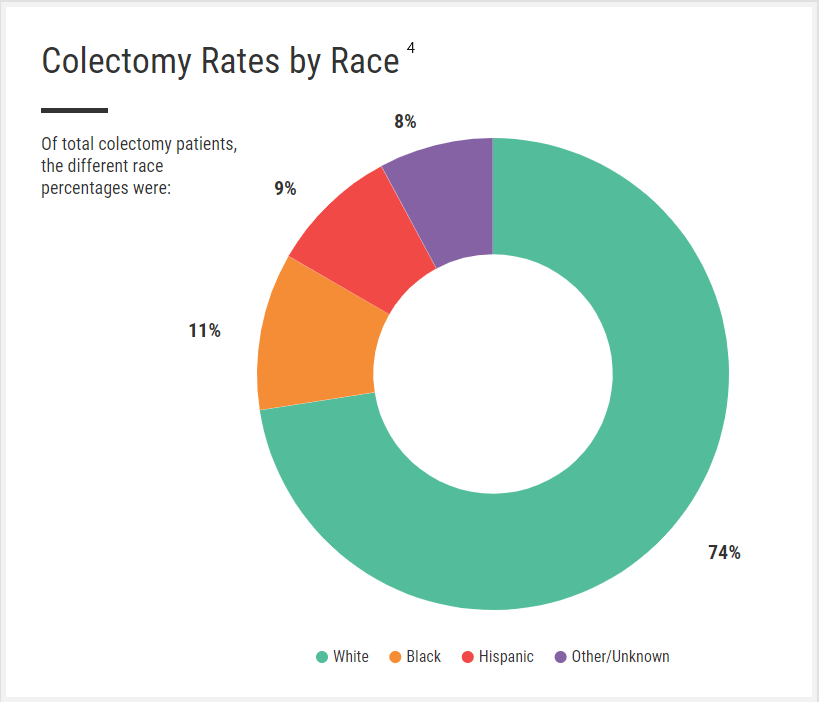

Of total colectomy patients, the different race percentages were:

- 74% white

- 11% black

- 9% Hispanic

- 5% other/unknown race

Of the 59,531 patients undergoing abdominal hysterectomies, the mean age was 49.8 years consisting of 100% females.

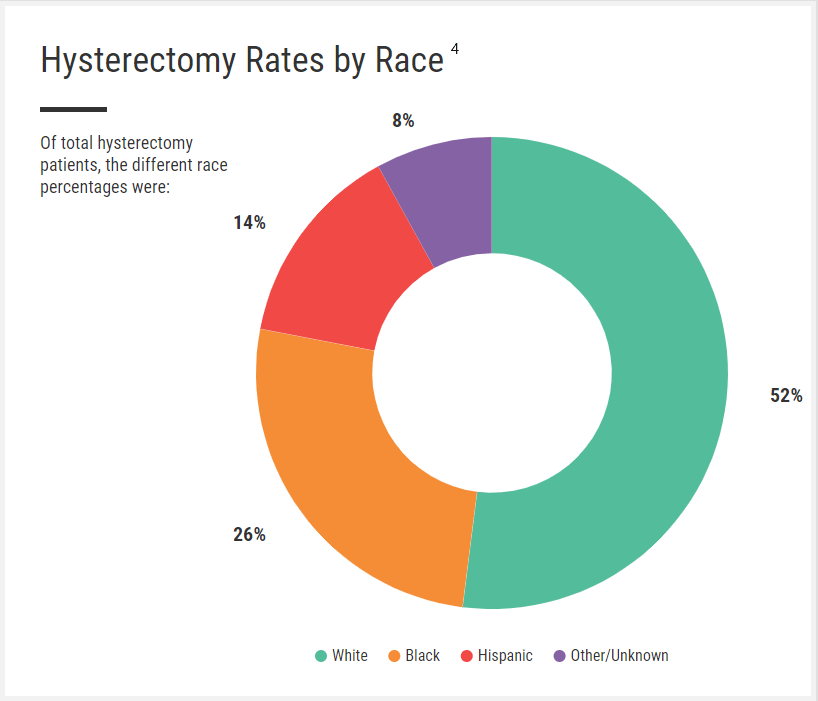

Of total hysterectomy patients, the different race percentages were:

- 52% were white

- 26% black

- 14% Hispanic

- 8% other/unknown race

Within 30 days of surgery, SSI rates were 2.55% for the colectomy group and 0.61% for the hysterectomy group.

For colectomy, black race (adjusted odds ratio [AOR], 0.71; 95% Confidence Interval (CI), 0.61-0.82) was associated with lower odds of SSI while no social risk factors in this study had statistically significant associations with SSI in the hysterectomy group. These results yielded inconsistent associations between social risk factors and SSI.

2. Material/Social Health Deprivation as a Risk Factor for SSI5:

In a case control study conducted at the Madison VA Hospital, the impacts of material and social health deprivation were evaluated as risk factors for SSI. Material deprivation included homelessness, inadequate self-hygiene, and an unsanitary home environment while social health referred to substance abuse or diagnosed mental disorders. Cases were defined as surgical patients that developed a National Healthcare Safety Network (NHSN)-defined deep and organ/space SSI between April and September, 2011. Nine cases and 17 control patients took part in the study.

The results were classified by the presence of only material deprivation, or combinations of material and social health deprivation. Material deprivation yielded results of Overall Risk (OR)=32.0, 95% CI 2.2 – 1558.0, P=0.0009 while combined material/social health deprivation resulted in OR=8.6, 95% CI [not calculable], P= 0.0034.

According to these results, material and social health deprivation were strongly associated with SSI.

3. Incidence of SSI Based on Location and Income6:

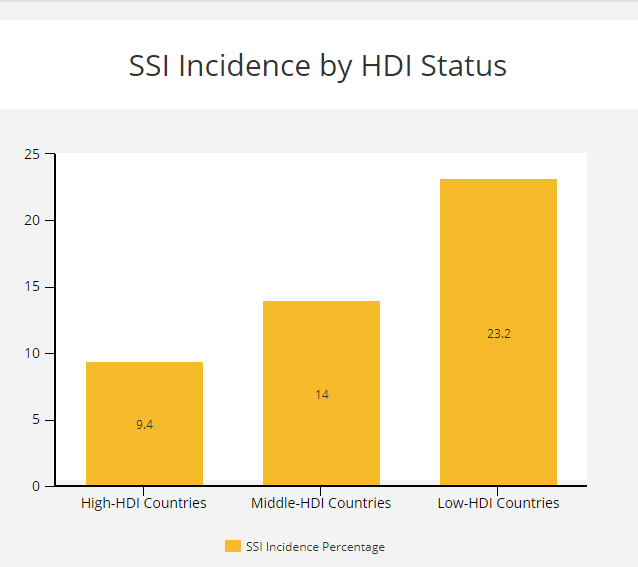

Results of a prospective, multicenter, international study including 12,539 patients undergoing elective or emergency gastrointestinal resection was published in the Lancet Infectious Diseases in 2018. The countries involved were classified as high, middle, or low income according to the United Nations Human Development Index (HDI). Thirty-day SSI incidences were investigated.

Overall, SSI incidence was 12.3% and varied between countries:

- 4% in high-HDI countries

- 0% in middle-HDI countries

- 2% in low-HDI countries (P <.001)

According to these findings, countries ranking lower on the HDI carry a disproportionately higher burden of SSI.

According to these studies, incidence of SSI may be associated with certain social factors and absent with others. The social factors mentioned above are only a few compared to many that could affect SSI risk. More studies are needed on socioeconomic status’ influence of SSI risk for the overarching question to be answered. A potential issue for additional studies could be that while other factors might be incorporated into SSI risk adjustment models, social risk factors are a separate adjustment that has to be made within the study.4

References:

1. Adler N, Newman K. Socioeconomic Disparities In Health: Pathways And Policies. Health Affairs.

https://www.healthaffairs.org/doi/full/10.1377/hlthaff.21.2.60. Published March 1, 2002. Accessed January 6, 2020.

2. Socioeconomic Status. American Psychological Association. https://www.apa.org/topics/socioeconomic-status/. Accessed January 6, 2020.

3. Masoud Z. Social Risk Factors Associated with Post-Colectomy Surgical Site Infections. https://www.infectiousdiseaseadvisor.com/home/topics/nosocomial-infections/inconsistent-associations-between-social-risk-and-complex-ssi-in-colectomy-and-hysterectomy/. Published December 10, 2019. Accessed January 6, 2020.

4. Qi AC, Peacock K, Luke AA, Barker A, Olsen MA, Joynt Maddox KE. Associations Between Social Risk Factors and Surgical Site Infections After Colectomy and Abdominal Hysterectomy. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2(10):e1912339. Published October 2019. Accessed January 6, 2020.

5. McKinley L, Duffy M, Matteson K, Crnich C. Deprivation Is a Risk Factor for Surgical Site Infection. American Journal of Infection Control. 41(6):S4-S5.

6. Paridon B. Incidence of Surgical Site Infections Highest in Lower-Income Countries. Infectious Disease Advisor. https://www.infectiousdiseaseadvisor.com/home/topics/nosocomial-infections/incidence-of-surgical-site-infections-highest-in-lower-income-countries/. Published March 16, 2018. Accessed January 6, 2020.