Vascular Access Devices (VADs) are more prevalent than ever, with some reports estimating that at any point in time there may be 5 million patients living with a VAD.[1] These patients may either be in the hospital receiving care or at home receiving longterm care, and while VADs offer flexibility to patients, VADs still have a large impact on patient quality of life.

What Day-to-Day Challenges Do Patients Living with Long-Term VADs Face? Repeated peripheral venipuncture can be a major source of anxiety and pain for patients, so VADs may be a welcome alternative.[2] However, having a VAD creates other challenges, as some patients may feel their VAD is a burden to their daily lives.

“A home health nurse needed to come out twice a week to change the dressing. That involved sterilizing the area and changing the dressing—probably about thirty minutes worth of activity. Every day the port needed to be flushed with saline and heparin. I always had two tubes just hanging out of my chest, which I never liked. I had to find a way to tuck them into my bra so they just didn’t dangle there.”[3] – Emily, VAD patient

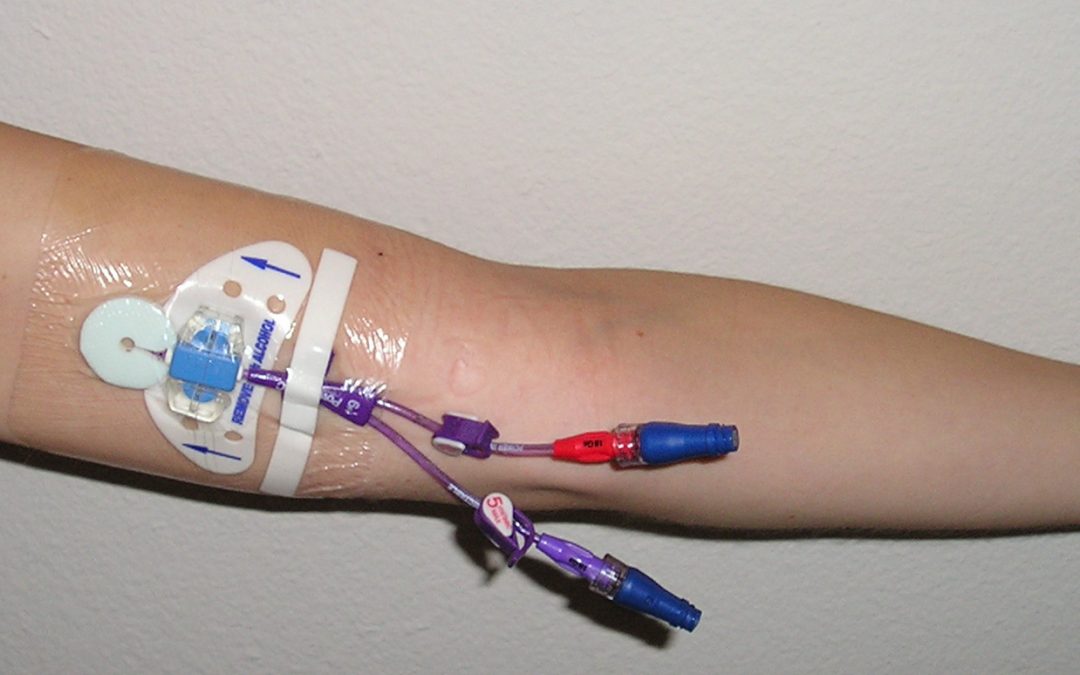

Besides being a visual reminder of serious illness,[4] daily activities such as showering may prove troublesome with a VAD. Recent studies have indicated that one of the most substantial sources of catheter-related infections in patients with central venous access is tap water. Because of this, many clinicians advise their patients to keep their catheters dry and to refrain from showering in order to minimize infection. Many patients find this impractical and may shower anyway or take baths instead.[3]

While patients may cover their catheters in attempt to prevent infection, they do so by covering their VAD in plastic wrap or plastic bags, which is inconsistent at keeping the exit site wound dry and sterile, causing infection.[5] 50% of patients with VADs experience complications, some of which are life threatening,[6] as morbidity rates in patients with VADs are at least 10%.[1]

VAD Dressings and Risk of Infection

The 2016 Infusion Therapy Standards of Practice recommend that VAD dressings be changed and firmly secured every 5-7 days. If dressings are loose or dislodged, they must be changed immediately.[7] Yet, commercially available dressings have surprisingly limited durability, with studies finding that 75% of CVC dressings last less than 48 hours and only 3% of dressings last a full seven days.[8]

Dressing disruption has been shown to be a major risk factor for CRBSI.[9] Independent of other factors, the risk of CRBSI increased more than three times after the second dressing disruption and by more than ten times if the final dressing was disrupted.[9] It is estimated that approximately 2 million patients develop a Hospital Acquired Infections (HAI) every year,[10] and that in acute care hospitals in the United States, HAIs lead to costs totaling anywhere from 96 to 147 billion dollars annually.[11]

While insertion location, type of dressing, and patient can all affect dressing loosening and dislodgement, it is imperative that dressings stay secured.

Minimizing infection risk is an essential part of optimizing “The Triple Aim” of the Affordable Care Act. Eloquest Healthcare is committed to providing solutions that can help you reduce the risk of conditions like a central line-associated bloodstream infection (CLABSI) and post-operative wound contamination.

References:

1. Longfield V. Cost issues and quality issues associated with line maintenance. Presentation at St. Luke’s Hospital Institute for Health Education; June 22, 2001; Chesterfield, Missouri.

2. Chernecky C. Satisfaction versus dissatisfaction with venous access devices in outpatient oncology: a pilot study. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2001;28:16131616.

3. Emily C, personal communication, November 8, 2018.

4. Kelly, L. The Experience of patients living with a vascular access device. Br J Nurs. 2017;26:19.

5. Do AN, Ray BJ, Banerjee SN, et al. Bloodstream infections associated with needleless device use and the importance of infection-control practices in the home health care setting. J Infect Dis. 1999;179:442-448.

6. Macklin, D. Developing a Patient-Centered Approach to Vascular Access Device Selection. Topics in Advanced Practice Nursing eJournal. 2005;5:3.

7. Vascular Access Device Management. In: Infusion Therapy Standards of Practice. J Infus. Nurse. 2016.

8. Richardson A, Melling A, Straughan C. Central venous catheter dressing durability: an evaluation. J Infect Prev. 2015;16:256-61.

9. Timsit, JF, Bouadma L, Ruckly S, Schwebel C, Garrouste-Orgeas M, Bronchard R, Calvino-Gunther S, Laupland K, Adrie C, Thuong M, Herault MC, Pease S, Arrault X, Lucet JC.Dressing disruption is a major risk factor for catheter-related infections.

10. Stone PW. Changes in Medicare reimbursement for hospital-acquired conditions including infections. Am.

11. Marchetti A, Rossiter R. Economic benefit of healthcare-associated infection in US acute care hospitals: societal perspective. J Med Econ. 2013;16:1399-1404.