Welcome to a new 3-part series focusing on SSIs. SSIs are the most common type of hospital-acquired infection (HAI). They occur an estimated 160,000 to 300,000 times per year and account for more than 20% of all HAIs.1

And while the negative clinical outcomes associated with SSIs (ie, morbidity and mortality) are commonly known, there is little consensus on the financial consequences to the hospital.2 In fact, the resulting financial burden to the US healthcare system is substantial. While costs of an SSI vary widely based on the degree of infection and the site of surgery, the estimated average cost of an SSI can be more than $25,000, increasing to more than $90,000 if the SSI involves a prosthetic implant.3 Overall, SSIs cost the US healthcare system an estimated $3.5 to $10 billion annually.1

The finding that up to 60% of SSIs are preventable has made SSI a primary target of institutions’ quality control measures and a key “Pay-for-Performance” metric.1 The associated “hard costs” cited above aren’t the only financial consequences faced by institutions caring for patients with SSIs. Since 2008, the US Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) are no longer reimbursing hospitals for HAIs like SSI.4 Not surprisingly, SSI prevention has become a critical objective for institutions nationwide.

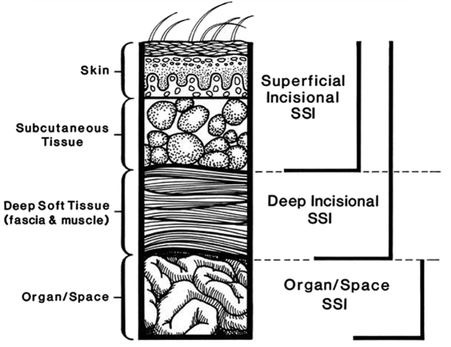

The National Healthcare Safety Network (NHSN), of the Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), is the nation’s most widely used healthcare-associated infection tracking system and the largest HAI reporting system in the US. The NHSN’s Patient Safety Component Manual lists 3 types of SSIs: 5

- Superficial incisional – Involves only skin and subcutaneous tissue of the incision

- Deep incisional – Involves deep soft tissues of the incision (eg, fascial and muscle layers)

- Organ/Space – involves any part of the body deeper than the fascial/muscle layers, that is opened or manipulated during the operative procedure

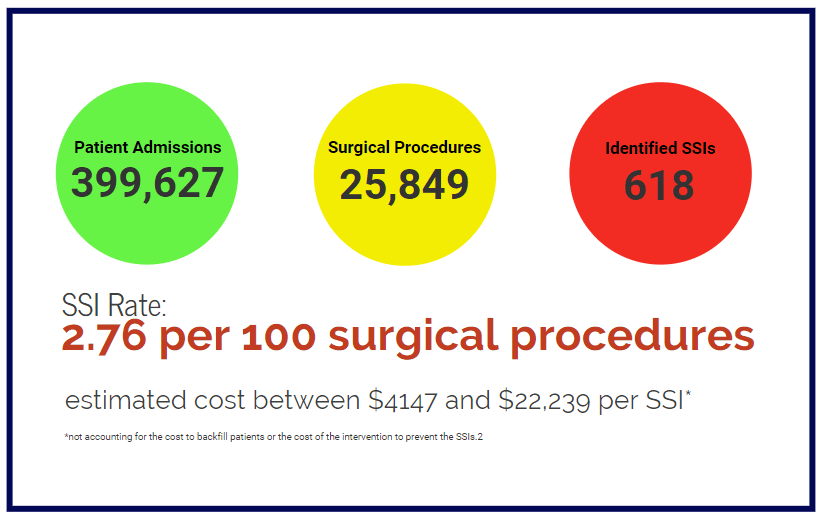

While SSIs have been shown to increase health care costs, few studies have conducted an analysis from the perspective of hospital administrators. Shepard et al completed a retrospective study to determine the change in hospital profit due to SSIs. The study was performed at four of The Johns Hopkins Health System acute care hospitals in Maryland.2

Over the 3-year study period, there were 399,627 inpatient admissions, 25,849 surgical procedures of interest, and 618 SSIs identified, resulting in an SSI rate of 2.76 per 100 surgical procedures. The data suggested that the net loss in profits due to SSIs for The Johns Hopkins Health System was between $4147 and $22,239 per SSI, not accounting for the cost to backfill patients or the cost of the intervention to prevent the SSIs.2

The study concluded that clinicians can spur hospital executives to invest in costly interventions or technology aimed at the reduction of SSIs by providing a cost-benefit analysis. When conducting such an analysis, it is crucial to use proper financial terminology. As there is an increasing need for additional infection prevention initiatives, which tend to require additional funding, it is imperative that care is taken in presenting accurate financial figures to maintain the financial well-being of health care institutions and promote the safety of patients.2

Minimizing infection risk is an essential part of optimizing “The Triple Aim” of the Affordable Care Act. Eloquest Healthcare is committed to providing solutions that can help you reduce this risk.

Read part 2 of this series, “Emerging Trends in SSI Prevention.”

References: 1. Ban KA, Minei JP, Laronga C, et al. American College of Surgeons and Surgical Infection Society: Surgical site infection guidelines, 2016 update. J Am Coll Surg. 2017;1:59-74. 2. Shepard J, Ward W, Milstone A, Carlson T, Frederick J, Hadhazy E, Perl T. Financial impact of surgical site infections on hospitals: the hospital management perspective. JAMA Surg. 2013;148(10):907-914. 3. Berríos-Torres SI, Umscheid CA, Bratzler DW, et al. Healthcare infection control practices advisory committee. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention guideline for the prevention of surgical site infection, 2017. eAppendix. JAMA Surg. Published online May 3, 2017. 4. Stone PW. Changes in Medicare reimbursement for hospital-acquired conditions including infections. Am J Infect Control. 2009;37:17A-18A. 5. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/nhsn/pdfs/pscmanual/9pscssicurrent.pdf. Accessed 04/17/18.