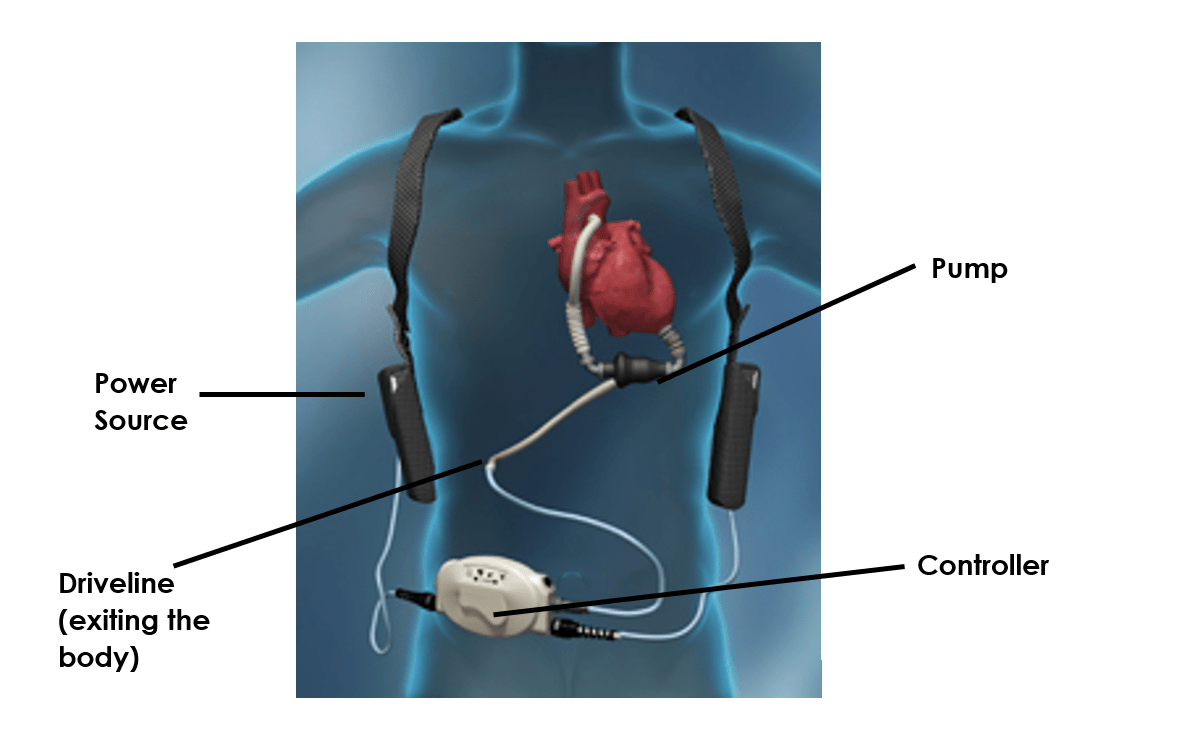

The previous blog of this 2‐part series focused on Left Ventricular Assist Devices (LVADs), including the prevalence of use, the types of patients treated, and the associated risks of LVAD‐associated infections. (View Blog 1 of 2) Part 2 of the series will focus on minimizing driveline infections once the patient goes home.

LVADs have revolutionized treatment of advanced heart failure and offer an acceptable quality of life for longer‐term therapies (ie, bridge to transplant, destination therapy, bridge to recovery).1 With these indications, the number of LVADs implanted each year continues to rise because the devices have been shown to improve survival.2

As Blog 1 of this series presented, protection of the LVAD driveline is critical because driveline infections are the most common type of LVAD‐associated infection.2,3 In a landmark trial using a first‐ generation LVAD (REMATCH), the prevalence of driveline infections varied from 14% to 28%.4 Infections associated with LVADs, which are meant to improve quality of life, can include hospitalization, need for reoperation, increased risk of stroke, and delay in transplantation.2

Because the patient and/or their caregiver is responsible for maintenance of their LVAD once at home, proper at‐home care and maintenance is critical. Infection is a major complication associated with LVAD therapy, with reported rates ranging from 25% to 80%.5

Clearly, at‐home training for LVAD maintenance is of utmost importance in caring for the driveline exit site and proper dressing guidelines. As a clinician who might be educating patients and caregivers, it is important to follow certain key LVAD driveline management guidelines.6 First, be sure to follow your institution’s protocol for driveline exit site care. Also, recognize that patients with an LVAD can still move freely and perform routine activities, but instruct them that there are precautions they must take to protect the driveline. Stress the importance of keeping the driveline exit site clean and free of infection. Some driveline exit care patient tips are included in the table below.6

Driveline Exit Care Tips for Patients

- Be careful not to twist, kink or pull on the driveline.

- Be sure that your controller is secure, so there is less risk of it falling and pulling on your driveline.

- Make sure the driveline doesn’t get pulled or snagged.

- If you keep your controller inside a zippered bag, make sure the driveline doesn’t get caught in the zipper.

- Regularly and carefully, wipe any dirt or grime off the driveline with a damp cloth.

- Avoid getting the driveline wet, especially right at the exit sie.

- Be careful around pets and children so they don’t accidently damage the driveline or other equipment.

Guidelines for dressing changes at home are also important. Again, follow your institution’s protocol for dressing change guidelines (ie, “sterile” technique, frequency of dressing changes, etc). Some typical guidelines to give patients and caregivers often include6:

- Wash hands before starting a dressing change.

- Never put ointments, powders, or lotions on or around the exit site unless instructed to do so.

- Follow the LVAD team’s directions on how often to change the dressing, following strict “sterile technique” every time you change the dressing or touch the exit site area.

- Typically, the driveline exit site is cleansed with an antiseptic agent such as chlorhexidine and dressed in a sterile fashion either daily or weekly. Then the site is usually stabilized with a driveline securement device. While there is currently no standard protocol for changing driveline dressings, an effort is being made to evaluate the convenience and efficacy of ready‐made dressing kits.3

- Contact the LVAD team right away if there is any redness, swelling or drainage around the exitsite, or when experiencing pain or a fever. These are all signs of possible infection.

Many protocols recognize that dressing integrity between scheduled changes can’t be accomplished by the dressing alone. The superior adhesiveness of Mastisol® Liquid Adhesive has been clinically demonstrated. Using Mastisol:

- Reduces the likelihood of dressing or device migration or accidental removal

- Minimizes the risk of infection by creating a lasting occlusive dressing barrier

Trauma at the exit site of the driveline promotes the onset and maintenance of an inflammatory process and local infections. Avoiding excessive mobilization of the driveline will likely reduce the incidence of infections at the exit site and improve the quality‐of‐life of the patient.7 The use of a gentle, effective adhesive remover can minimize this friction/pulling at the skin during dressing changes.

To prevent skin damage from repeated application and removal of LVADs, use Detachol® Adhesive Remover. Detachol can play a significant role in assuring clinicians that they are doing everything possible to reduce the risks to patients and costs to healthcare providers that may result from the improper removal of tapes, dressings, and devices.

Using Detachol:

- Reduces the risk of Medical Adhesive Related Skin Injury (MARSI)8

- Removes adhesive residue/bacteria9,10

- Provides a non‐irritating, alcohol/acetone‐free formulation

- Offers chlorhexidine gluconate (CHG) compatibility11

Dressing integrity is crucially important once an LVAD patient returns home. Because patients and/or their caregivers are responsible for maintenance of their LVAD once at home, proper training of dressing maintenance as well as the risks of non‐adherent dressings is essential. Follow your hospital or clinic’s protocol for specific directions and recommendations for exit site care.

For more information about Mastisol or Detachol, please contact your sales consultant or Eloquest Healthcare®, Inc., call 1‐877‐433‐7626 or visit www.eloquesthealthcare.com.

Minimizing infection risk is an essential part of optimizing “The Triple Aim” of the Affordable Care Act. Eloquest Healthcare is committed to providing solutions that can help you reduce the risk of conditions like a central line‐associated bloodstream infection (CLABSI) and post‐operative wound contamination.

Don’t miss out on our next 3‐part blog series on Surgical Site Infections (SSIs), subscribe today!

References: 1. American Heart Association. http://www.heart.org/HEARTORG/Conditions/HeartFailure/TreatmentOptionsForHeartFailure/Devices‐and‐Surgical‐ Procedures‐to‐Treat‐Heart‐Failure_UCM_306354_Article.jsp#.Wly709‐nGUk/ Accessed 01/11/2018. 2. Yarboro LT, et al. Techniques for minimizing and treating driveline infections. Ann Cardiothorac Surg 2014;3(6):557‐562 3. Leuck AM. Left ventricular assist device driveline infections: recent advances and future goals. J Thorac Dis. 2015;7(12):2151‐2157. 4. Hernandez GA, Breton JD, Chaparro SV. Driveline infection in ventricular assist devices and its implication in the present era of destination therapy. Op J Card Surg. 2017;9:1‐6. 5. Nienaber JJ, et al. Clinical manifestations and management of left ventricular assist device‐associated infections. CID. 2013;57:1438‐1448. 6. MyLVAD. https://www.mylvad.com/discussions/lvad‐driveline‐management. Accessed 01/11/2018. 7. Baronetto A, Centofanti P, Attisani M, Ricci R, Mussa B, Devotini R, Simonato E, Rinaldi M. A simple device to secure ventricular assist device driveline and prevent exit‐site infection. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg. 2014;18(4):415‐7. 8. McNichol L, Lund C, Rosen T, et al. Medical adhesives and patient safety: state of the science. Consensus statements for the assessment, prevention, and treatment of adhesive‐related skin injuries. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs. 2013;40:365‐80. 9. Berkowitz DM, Lee W‐S, Pazin GJ, et al. Adhesive tape: potential source of nosocomial bacteria. Appl Microbiol. 1974;28:651‐54. 10. Redelmeier DA, Livesley NJ. Adhesive tape and intravascular‐catheter‐associated infections. J Gen Intern Med. 1999;14:373‐5. 11. Ryder M, Duley C. Evaluation of compatibility of a gum mastic liquid adhesive and liquid adhesive remover with an alcoholic chlorhexidine gluconate skin preparation. J Infus Nurs. 2017;40(4):245‐52.