Eloquest Healthcare is excited to welcome Gwen Borlaug, MPH, CIC, FAPIC to the Eloquest Healthcare Blog! Gwen worked at the Wisconsin Division of Public Health (DPH) as the Director of the Healthcare-Associated Infection Prevention Program and as an infection prevention epidemiologist. She launched a statewide public health initiative to reduce surgical site infections, using a surgical care champion to provide peer-to-peer learnings to surgeons and surgical teams in Wisconsin hospitals. She also served as the MRSA epidemiologist and subject matter expert.

She has been an infection preventionist for 22 years. She received an APIC Heroes of Infection Prevention Award and a Chapter Leadership award in 2010 and became an APIC Fellow in 2017. She is currently an independent infection prevention consultant.

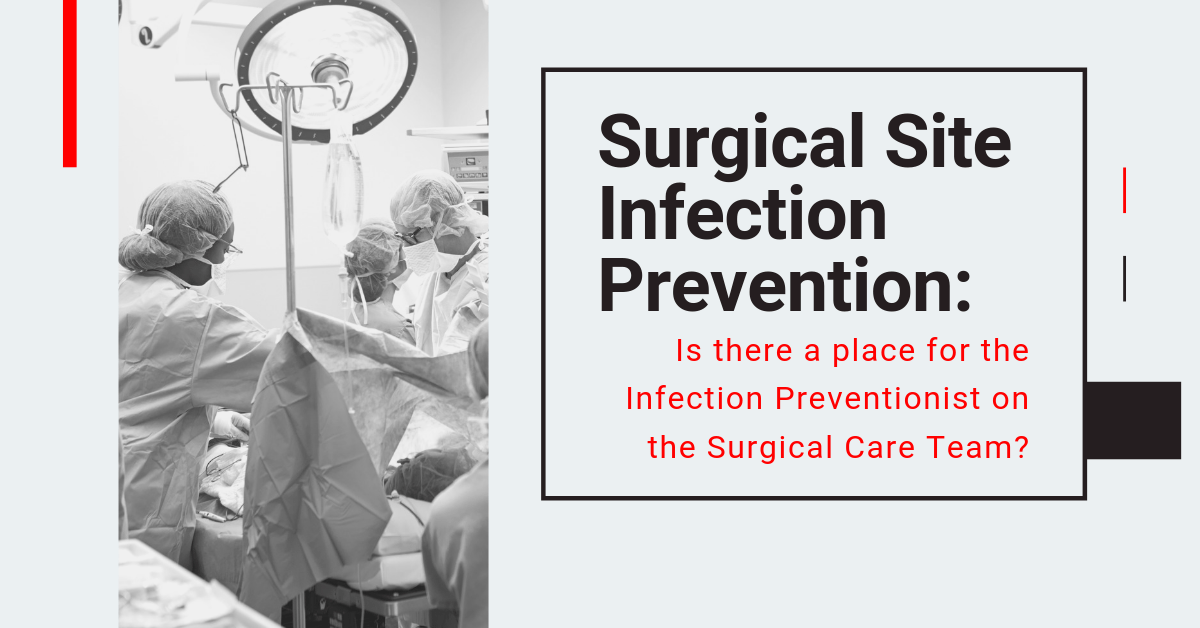

Surgical Site Infection Prevention: Is there a place for the Infection Preventionist on the Surgical Care Team?

Surgical site infections (SSI) among inpatients are tied with healthcare-associated pneumonia as the most frequently occurring healthcare-associated infection (HAI) in the United States, with an estimated 157,000 SSIs reported during 2011[1]. Approximately 2 percent of inpatient surgical procedures performed in the U. S. result in an SSI, and the estimated cost to treat a single SSI ranges from $19,000 to $22,000[2].

Because SSIs continue to significantly impact patient safety and healthcare costs, infection prevention programs must include robust SSI prevention strategies to promote high quality surgical care. Infection preventionists (IPs) must play a key role in SSI prevention, but often times believe they lack the knowledge and skills to support their surgical colleagues, and thus refrain from interacting with them to implement comprehensive SSI prevention programs. IPs may even feel intimidated by the unique and complex operating room environment.

During my tenure as the Director of the Wisconsin Division of Public Health HAI Prevention Program, I worked with scores of IPs on various projects, and visited more than 30 hospital surgery centers during our statewide SSI prevention project. These experiences lend evidence that IPs DO possess unique skills and abilities that are vital to any SSI prevention effort; IPs cannot be excluded from these activities but rather must be actively engaged with their surgical teams to ensure the contemporary SSI prevention bundle is optimally adopted in their facilities.

Two areas of expertise IPs have to offer their surgical colleagues in SSI prevention efforts come to mind.

SSI Surveillance

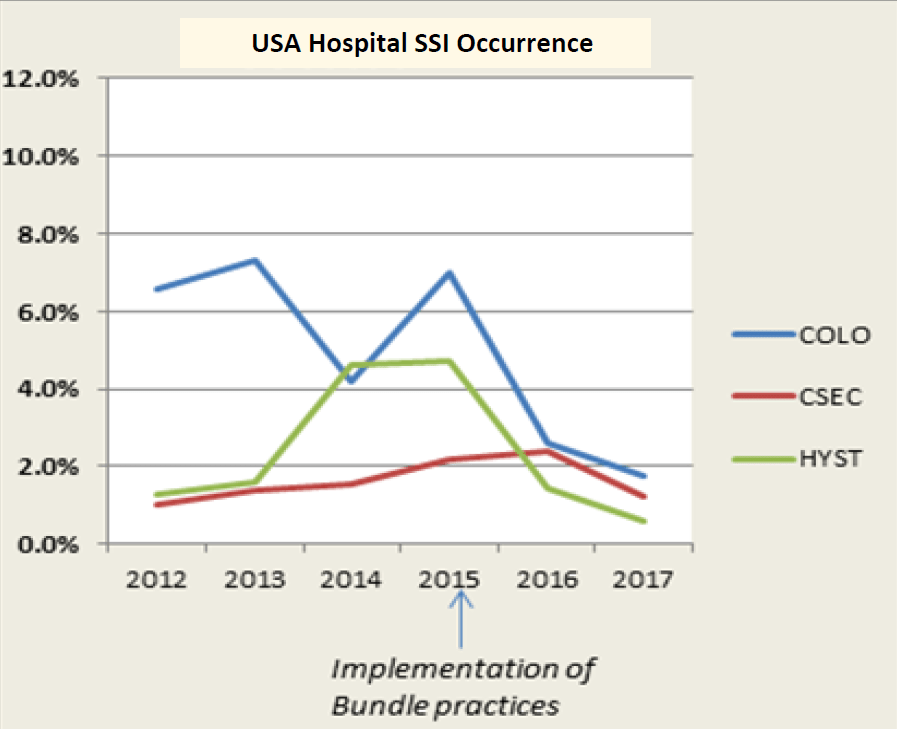

The cornerstone of infection prevention is surveillance. One cannot know what to prevent, how to prevent, or whether prevention efforts work to mitigate infection risk unless surveillance for SSI events is conducted. Studies have long demonstrated that active surveillance with feedback to frontline staff and other stakeholders can help reduce SSI incidence[3]. IPs are trained in methods of data collection using standardized case definitions, they can identify relevant data sources and apply epidemiologic principles and practices to summarize, analyze, interpret and meaningfully present SSI data to surgical teams regarding SSI trends and populations at highest risk, which in turn guides prevention efforts. SSI surveillance represents a facet of SSI prevention that IPs are uniquely and well-equipped to bring to the table.

Performance Improvement and Implementation Science

As individuals tasked with transforming clinical practice to improve patient outcomes, IPs have developed competency in performance improvement methodologies that, according to the APIC (Association for Professionals in Infection Control and Epidemiology) competency model, include “assessing performance, setting achievement goals, using data to initiate changes, incorporating human factors engineering, and developing measures that will ensure sustainability of the improvement[4] .” IPs can fulfill these critical functions as they work to implement evidence-based SSI reduction strategies with their surgical care teams.

Finally, an important characteristic of IPs is that they are historically excellent learners. Because the profession of infection prevention is derived from other vocations such as nursing, clinical laboratory science, microbiology, and epidemiology, the requisite knowledge and skills to become a proficient IP are largely learned in an apprentice- type situation, with veteran IPs teaching their novice colleagues. Although these other vocations provide contextual knowledge and background for the incoming IP, the learning curve during the first few years of IP practice is steep and challenging. Furthermore, the science of infection prevention is broad and dynamic and IPs must continue to learn the latest in technology and evidence-based practices, and develop new skills throughout their careers.

So, although the majority of IPs may not initially have knowledge or experience in the surgical sciences or operating room culture, their ability and willingness to learn will serve them well.

I have also discovered during my visits with surgeons and OR staff that these individuals are more than eager to share their knowledge, skills, and experience with IPs, and so my message to IPs is this: Ask OR staff to teach you. Ask to have an occasional presence in the OR so you can see firsthand how surgical teams function. Ask them to help you understand their procedures and processes of caring for the surgical patient. Ask, ask, and keep asking. These encounters with the surgical environment and OR staff as initial learning steps will bolster your confidence and will aid in the development of collaborative relationships with your surgical colleagues.

This is only a preface to a broader discussion of the role of the IP in SSI prevention. We invite you to view our on-demand educational webinar, titled, “The Infection Preventionist’s Role in Preventing Surgical Site Infections: How to Develop Effective Partnerships with the Surgical Care Team”. Register here!

We will expand our discussion of IP support activities and add topics such as the current SSI bundle, available learning resources, and the role of additional members of the SSI prevention team. We hope to have you join us!

References

1. Magill, S.S., et al. Multistate point-prevalence survey of health care-associated infections. NEJM 2014;13: 1198-1208.

2. Zimlichman, E., et al. Healthcare-associated infections: A meta-analysis of costs and financial impact on the US healthcare system. JAMA Intern Med 2013;22: 2039-2046.

3. Condon R., et al. Effectiveness of a surgical wound surveillance program. Archives of Surgery 1983;3: 303-307.

4. Billings C., et al. Advancing the profession: An updated future-oriented competency model for professional development in infection prevention and control. AJIC 2019;6: 602-614.